Chris Durban doesn’t need introducing. She’s a member of ATA and SFT, a Fellow of ITI, and an active member of the translation community. If you’re a successful translator, chances are you’ve already heard of her. However, if you’re still working your way up the career ladder, then stop what you’re doing right now and get a copy of "The Prosperous Translator” co-written by her. It’ll make your climb easier.

Chris Durban doesn’t need introducing. She’s a member of ATA and SFT, a Fellow of ITI, and an active member of the translation community. If you’re a successful translator, chances are you’ve already heard of her. However, if you’re still working your way up the career ladder, then stop what you’re doing right now and get a copy of "The Prosperous Translator” co-written by her. It’ll make your climb easier.

I was very excited to have the opportunity to chat with Chris in September at The Cracow Translation Days 2013. She may be an excellent translator, but she’s also a focused business person with a quick wit. And she knows how to work the room! If I knew how she does it, I’d bottle it and sell it to other translators. Unfortunately, I don’t, so for now, please enjoy reading her insights into the translation profession. And don’t forget to enter my giveaway for a chance to win a copy of "The Prosperous Translator”!

Q: You’ve had a successful career in translation. Why did you decide to become a translator?

I grew up in rural America but had itchy feet; I wanted to get out and see the world. And thanks to language classes in primary and secondary school, I especially liked the idea of going to France. But to live there, I needed a visa, so when I was 18 I registered as a student at the University of Paris (which was much easier to do in those days). That student visa allowed me to work part-time, which was fortunate since I also needed to finance my studies. And the economy was relatively buoyant, so I was able to string together a whole range of part-time jobs—from candle-making (yes, I’m crafts-y) to photocopying, tutoring and childcare. I worked as a tour guide. I worked in a supermarket. One summer I packed fishsticks at the Findus plant in Hammerfest in northern Norway. But as my studies progressed, it became clear that I needed a better job to support myself.

One day I saw an ad in the paper for a part-time financial translator. As part of my university course, I’d had a few classes in business and financial translation, although with hindsight the content and teaching were both light-years from real translation. Yet I was now pushing age 22, with a few translation classes under my belt and at least another year of studies to go and I had the rent to pay, so I was really keen to get that job. I typed up a CV (on a typewriter: personal computers had not yet been invented) and went in for an interview.

The interview went reasonably well, and after a few questions I was ushered into a room to do a test translation. The plot thickens here. That is, I recall having tucked a paperback business/financial dictionary in my handbag earlier that morning and after some (minor) soul-searching sneaked it out when no one was looking. Even so, I was very surprised when they called me back to say I’d got the job.

OK, I was no airhead and certainly a hard worker, but at that time I had no idea about financial markets, monetary policy, economics, banking or any of the content I was supposed to be translating. Clueless. Fortunately, I was on a team that included the authors of my texts—French financial analysts with offices just down the hall, so I could duck in and ask for help as needed. That was a lifesaver. And the French bankers’ association offered night classes for employees, which were also useful. In those days, too, there was less time pressure: deadlines were far more flexible. Actually, nobody in the bank seemed to know what purpose the investment reports I was translating were to serve (perhaps "to make the bank look international”? ventured one young fellow), and the translations generally came out two or even three weeks after the original. That alone would be unthinkable nowadays, when investment advice has to be published within the hour or half-day. How times change!

At any rate, the job was a great opportunity to learn about the forces driving the French economy, the structure of the private sector (the reports I was translating reviewed industries and companies in great detail) and—the icing on the cake—life behind the scenes in a bank in France.

I ended up working there for about eight years, during which I met a lot of young hires, mostly financial analysts. Their standard career path was gradual promotion to the senior analyst track or, possibly, moving on to become fund managers in other banks and companies. At which point they would occasionally phone me if a translation was needed. We’d call that "networking” today: however little I knew, I’d lunched with them in the bank cafeteria (where my sincerity and general interest in whatever was going on no doubt stood me in good stead). Above all, I was their only contact with the world of translation. So without even trying, I started getting clients.

By then, I’d finished my studies and got a permanent visa and work permit. Out of habit, I continued to take night courses—some language and some other things. And for a while I was very happy working part-time as an in-house translator and freelancing on the side.

Then my division got a new boss, an ex-military gentleman. The guy was unbelievable—I believe the technical term is "male chauvinist pig cloned with martinet”—and I felt it was time for me to move on. Fortunately, French labour legislation allowed employees to take two years off to set up their own business, so I filled out the forms and took the plunge. And after the two years were over it was clear I was not going back: working for yourself is so much more enjoyable.

Q: Building a successful career is a long process that requires a lot of commitment and hard work. Can you tell us about some of the highlights to date?

I’ve always been a go-getter (earnest/nerd also come to mind) and financial independence has always been high on my agenda. (It’s difficult to leave rural America without saving up a nest egg.) But the transition from a salaried position to working freelance was definitely a major development for me. Building my own business—finding clients and working with them—didn’t seem particularly daunting and I actually enjoyed most of it. But the shift itself was a big change.

Not to date myself, but I also remember buying my first personal computer, an Apple II (screen: orange letters glowing on a black background).

And I recall my first years as a member of the SFT (Société française des traducteurs). At the time the association seemed much more inward-looking than it is now; the officials were distinctly "upper class” from my perspective and no one was particularly welcoming to new members—least of all a country cousin like me. In those days they were also into very pricey (for me and other young translators) lunches and dinners with a great deal of speechifying. All of which has changed a lot over the years—a very welcome change that accounts for a lot of the association’s growth, in my view.

One of the first specialist training events I attended was a workshop on business and financial translation organised by ITI in London. I recall taking an overnight train, staying in a cheap hotel, counting my pennies and finding the whole experience very stressful. However, I did meet people who have since become close friends and good colleagues. And I started thinking long and hard about how I really would have to buckle down and master the content of what I was translating.

A while later—in the early nineties—I became an active contributor to Flefo, the internet’s only watering hole for translators at that time, and met more future friends and colleagues that way. Flefo hosted some very animated debates, and when I finally met up with people I’d crossed swords with (or agreed with) in online posts, it was kind of exhilarating. That, plus trips to see my family in the United States, led me to attend ATA conferences and ultimately join the US association.

I was involved with other associations, too, and to raise funding for one project agree to organize a training event for financial translators with the Paris Stock Exchange, who were one of my early clients. The Bourse and its member firms clearly had a need for specialized translators; a lot of the work being churned out was woefully amateur. So I suggested holding a training day and they agreed. They supplied the room and speakers, and I did the coordinating.

That has since morphed into the Summer School for Financial Translators organized every two years by SFT. ASTTIholds it in Switzerland in alternate years. It’s a lot of work to put together, but also terrifically motivating to see such skilled people getting together in a room to hear presentations by senior executives and economists—non-linguists who then go back to their respective communities impressed by the fact that there are specialized translators. Which is something they didn’t necessarily realize before if they’d been dealing solely with bulk vendors.

Q: You’re a very successful translators and an inspiration to thousands of translators around the world. Where do you get the energy to serve demanding clients every day and at the same time to inspire other translators?

I actually enjoy the work and the contacts; I find them energizing. I’m also lucky in that I don’t sleep very much (a personal habit). Or make that: when necessary, I can adjust my sleeping habits.

Here’s an example: over the past few years I’ve been working ten days every 2-3 months from the East Coast of the United States, while visiting family. Given the 6-hour time difference between the East Coast and my office in Paris, I need to get up at 5.30 am to be available for my French clients at 11.30 am, because as a colleague quite rightly pointed out—and as I’ve realized myself, now—French customers like to speak to you before they head out to lunch, if only to be sure their job is in good hands.

The rest of the time I work on my own in my office in Paris, but with an external reviser and translation colleague so we can cross-check: two eyes good, four eyes better. Before that I worked with another translator in my office, although I was the person who dealt with clients, in addition to translating.

Initially a lot of our work consisted of translating investment reports, which I enjoyed because we’d built up expertise in that area and I had a good feel for the market. But at one point I observed that clients facing very large monthly bills—and given the volumes involved, ours were getting up there—would usually start shopping around for an in-house translator. It was a cheaper solution for them, or so they thought.

Since I didn’t want to go back into salaried employment, I decided to explore markets where, unlike investment reports, there was very little price pressure. For the record, money isn’t my sole driver, but when clients are paying more for your work, a number of problems are resolved right off the bat. For example, the texts you receive have usually been vetted pretty carefully. Moreover content is often something mission-critical or very important, which gives the buyer extra motivation to get it right—and gives me leverage to negotiate better working conditions and pay. Clients will definitely pay more for work where risk (to their image or bottom line) is concerned.

So I looked around and identified a few fields that looked promising—financial communications, for example, where every word is weighed four or five times before publication. By definition this brings you into contact with top people who—assuming you do a good job in a timely way and interact professionally—come to count on you. They pass your name around. Crisis management is another example: there is little or no price pressure, since when disaster strikes your client has no choice: something has to be done. There’s no real forward planning except tracking current events at all times, and there’s severe pressure on the translator to be able to step in and perform. But if your name is out there as someone who can deliver the goods in those situations you’re in good shape. Plus the jobs themselves are exciting and get the adrenaline flowing.

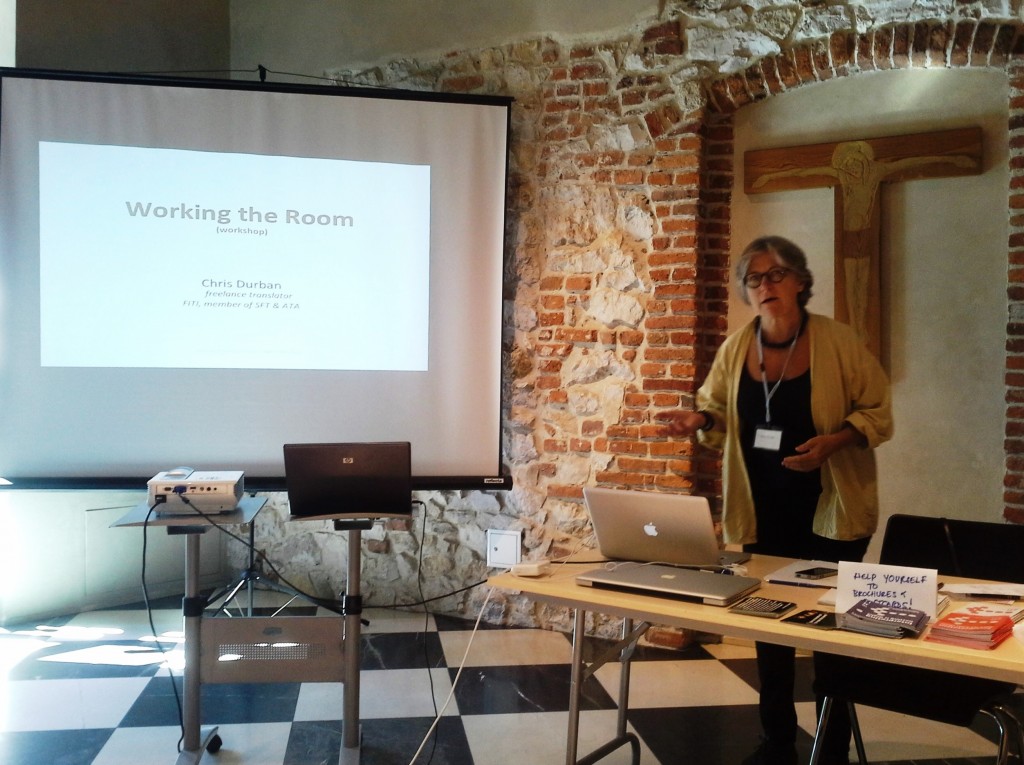

Chris delivering her masterclass on how to work with direct clients at the Cracow Translation Days 2013

I have a great deal of respect for my clients. Most are extremely good at what they do and a pleasure to deal with. Demanding clients are passionate about their work, and they expect you to be, too—which is just how I like it. And I admit to getting a wee bit impatient with translators who rail on endlessly about how stupid translation buyers are. Shall I be blunt? Very few clients are stupid. And sure, if you do meet up with one of those, you should give them a wide berth. By contrast, lots of clients are ignorant. But what does that mean? Well, that we—our profession—has failed to educate them about how we work and how they can spend their translation budget efficiently. So if you don’t like your clients, I’m sorry to hear that. But endless complaints suck the air out of the room: if clients have got potential, educate them. If they haven’t, put together a plan and go out and find some new ones. And then fire the no-hopers.

I make a living translating, but most of the other activities I get involved with are energizing in and of themselves. For example, I’ve always liked writing, and back in the Flefo days it was clear that some translators simply didn’t know how to run a business. So my Frankfurt-based friend Eugene Seidel and I suggested to Gabe Bokor, editor of Translation Journal, that we could write an advice column for translators. We called ourselves Fire Ant and Worker Bee, and initially wrote both the questions and the answers, which we tried to make witty and practical. To our astonishment, within six months we started getting real letters, and the flow continues to this day. The updated and revised compilation of these columns was published in book form as "The Prosperous Translator” in 2010.

Likewise, during my initial involvement in various translator forums, I noticed translators were fond of flagging poor translations, but often didn’t go further than that. This prompted me to start a client education column called "The Onionskin” in which I interviewed suppliers and clients to see precisely how these slipshod translations had come into being. The column ran in the ITI Bulletin and the ATA Chronicle and provided the raw material for the little "Getting it right” brochures, now available in 14 languages.

These days I’m very interested in master classes and specialist seminars for translators—a good way to learn from expert colleagues and stretch your mind. The Université d’été de la traduction financière that I mentioned earlier is an example, as are the Translate in the Catskills/Translate in Quebec events.

As long as all of these activities generate energy, I’m fine with them, although I’m now a bit more careful about getting overextended.

Q: A lot of translators have now turned to social media. What are your views on social networking? Is it a waste of time or an indirect marketing activity everyone should now engage in?

Interesting you should ask, because I’m of two minds. That is, when I look at peers who are heavily involved in social media, there are clearly some high-calibre writers and translators. But from my vantage point there also appear to be a lot of hangers-on—or perhaps I should say people whose focus isn’t all that clear to me. And whose translation skills I wonder about.

How about this: translators are often introverts who’ve chosen to focus on the written word rather than deal with other people. That can backfire if you get too isolated, which why I always encourage translators to get out of their caves and come down off the mountaintops to interact with clients—and the world, for that matter—no matter how scary it seems at first. Because it forces you to open your mind up to clients, their needs, their "voice”. Without that, you’ll have a very hard time producing really good work and you’ll also be dependent on others to find clients for you.

With those thoughts in mind, social media may look like a lot of networking and reaching out is involved. But I’m wondering now if some translators don’t use it as yet another excuse to stay in their comfort zone—among friendly, non-threatening peers or even "fans”—rather than push themselves to produce genuinely professional work. Seen this way, social media can be a lure, a time suck, a kind of mutual admiration society whose concrete spinoffs are not all that clear—unless, of course, you are selling products and services to fellow translators, in which case fair enough. After all, professional work happens in a professional environment.

OK, there are positive examples. Karen Tkaczyk, who heads ATA’s Medical Division and holds a PhD in chemistry, reports using social media to interact with chemists and contributes to forums in her area of expertise. She then becomes their go-to person for translation, which sounds like exactly where you want to be. I can also see interaction through social media as a source of intellectual stimulation. Which is all very good. But for other translators, it may mean staying in the (translation) family; they are not really reaching out, and I sometimes wonder if they aren’t in the equivalent of an echo chamber with a bunch of other friendly freelancers, and not reaching out to clients at all. Certainly not to direct clients.

I hope that doesn’t sound too harsh or cynical—and I’d love to be proved wrong.

Q: Finally, what advice would you give to experienced translators who would like to expand their portfolio of high-profile direct clients and be offered better paid and more prestigious projects?

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, I find working with direct clients gratifying because you’re in charge of your own work. Finding and securing good clients demands a different level of focus and dedication than simply churning out texts. You have to be prepared to provide premium service and go the extra mile; you have to be easy to work with, organized, and an extremely good writer and translator. And master your subject(s), of course.

By this time it should be clear that I don’t view translating as lifestyle. It’s a professional career that requires a lot of commitment and can’t be done sustainably on an ad hoc basis while, say, island-hopping in the South Pacific—however cool that sounds. For one thing, you have to stay on top of the fields you work in. Big investment there.

But it’s all part of a whole: once you start digging into any sector, you start understanding the big questions much better, which makes it easier to get excited about your text. That excitement helps you communicate better with your clients who, by definition, are passionately involved in the topic. And ultimately that’s how you gain access to profitable and interesting jobs. But you’ll only break into that lucrative circle if you’ve managed to position yourself on their radar screen. I’m starting to repeat myself here, but I guess the advice is that hard work, targeted the right way, is where to start.

Another piece of advice is to steer clear of crazy people, moaners and complainers. Being surrounded by them may be reassuring because it lets you stay within your comfort zone and empathize—after all, everyone has something she can complain about. But it’s not a productive way to build up your translation business or even spend your time, in my opinion.

Over the years, I’ve travelled to many countries and met a lot of translators who respond "yes, but…” when challenged to kick their practice into shape—which they claim they want to do. But they then proceed to stew in their own juices, postpone their makeover and find all sorts of reasons to stick with the status quo. Fair enough, if that’s what they want. But if you don’t take genuine pride and pleasure in being a translator—in actually doing the work—I can’t see you getting far with that approach.